In a world that really has been turned on its head, truth is a moment of falsehood.1 — Guy Debord

The questions that I am asked more than any others are, “What can we do? What can I do?” In the face of impending doom — which more and more people are beginning to dimly perceive, perhaps with Trump’s election serving as the proverbial canary in the coal mine — what can any of us do to help save ourselves from ourselves? The shortest answer I can give is the traditional socialist line: Educate, agitate, organize. Political dissidence in the forms of protests, civil disobedience, boycotts, sit-ins, teach-ins, strikes, and the like are important activities that I support and that I have participated in myself. These actions can and do produce worthwhile immediate effects, especially by catalyzing solidarity among participants. But, unfortunately, these actions will not succeed in producing the kind of overarching change that we so urgently need.

I want to be crystal clear about this: on their own terms, none of the above activities will, or even can, save us. They are still important, and we should still engage in them; remember, all life is lived under the growing shadow of certain death. But political dissidence aimed at reform rather than revolution is, at this point, largely a waste of our limited remaining time. (This is one reason why I and many others have been spreading the idea of a revolutionary, and admittedly unlikely, national general strike.) Historically speaking, it is simply too late for reform to accomplish anything meaningful. The event horizon for social collapse and probable human extinction was passed, at the latest, before anyone under the age of 50 was even born. Collapse is coming (it is already underway) — all that matters now is how we cope with it.

In other words, by every metric that matters for our survival as a species, 2017 will be worse than 2016. This will be true next month when the Super Bowl is played and when the Oscars are awarded. It will be true when the fireworks burst in July and when the new iPhone model is revealed in the fall. It will be true even if in the small circle of your privileged life things seem to stay about the same or perhaps improve.

This year will be worse than the last and, indeed, every year for the rest of your life, reader, will be worse than the year that preceded it because we are experiencing the death spasms of modern complex human society. These spasms are the result of the mutually constitutive and mutually reinforcing coincidence oflate capitalism and global warming. Very simply, what this means is that, as capitalism developed from its historical origins — particularly from the Industrial Revolution onward — it established the social conditions that, in turn, produced the physical conditions for global warming. And, as global warming worsens the physical conditions under which humans on Earth must exist, it will thereby exacerbate those social conditions from which it arose. This is the ultimate positive feedback loop, and there are only two ways out of it: a rapid transformation of human consciousness, or a rapid collapse of human civilization. (More on these below.)

But first, as a concrete and representative example of what I’m talking about, consider the history of theStandard Oil corporation. Founded in the 1870s, this private enterprise was organized for the purpose of extracting and refining oil for profit. Under the leadership of its founder, John D. Rockefeller, Standard Oil became exceptionally efficient at accomplishing its goals. Indeed, through successful efforts at bothhorizontal and vertical integration, Standard Oil came to control nearly the entire supply chain for and production process of oil. As a result, Standard Oil became a monopoly, and Rockefeller became thewealthiest man in world history.

Why does this matter? Well, in the early 1900s, the American government — as a response to the monopolies and robber barons of the Gilded Age — began, through public and legal action, to break up the corporations that had come to dominate American society. Standard Oil was no exception; it was fragmented by the Supreme Court into nearly 100 smaller companies. But, over time, these fragments reformed into massive corporations whose names remain familiar today: Amoco, BP (via acquisitions), Chevron, Exxon, Mobil, Sunoco. By the late 1990s, Exxon and Mobil had rejoined through one of the largest corporate mergers of all time. And now, President-elect Donald Trump has named Rex Tillerson, the CEO of ExxonMobil, as the Secretary of State for Trump’s incoming administration.

What I have left out of this narrative, of course, are the environmental effects that have accompanied the Age of Oil. We now know — and, indeed, we have for decades known — that the burning of fossil fuels releases into the air immense amounts of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane. And, because of these increased quantities of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the Earth is undergoing global warming. (Also worth mentioning are the knock-on effects from industries enabled by fossil fuels, like factory farming.) Global warming is, in fact, killing us. And it is killing us faster than we thought it would; indeed, the rate at which the planet is heating up is accelerating beyond all conventional expectations. Consider that, in just this past year, we have seen: an unprecedented streak of record high monthly temperatures; Arctic temperatures 50 degrees above their historic averages; sea ice levels at historic lows; the bleaching of coral reefs; the thawing out of microorganisms that will soon exhale enormous amounts of sequestered carbon dioxide; the decimation and extinction of animal and plant life at horrifying rates; andso much more.

We humans are not somehow standing outside of and above these events; we are enmeshed within them, and we are the generators of them. We are thoroughly ensconced in the Earth’s sixth mass extinction event, and we have at best ten or twenty years within which to take drastic, transformative, revolutionary social action that might prevent our extinction. For global warming is to humankind what the Chicxulub asteroid was to the dinosaurs — though that comparison is rather unfair to the dinosaurs, since they never saw their extinction coming.

This brings us back to Standard Oil and its mutant progeny, who, in raising from their resting place the liquefied remains of those long-dead dinosaurs, have doomed us humans to snuffing ourselves out with them. That we are killing ourselves and allowing ourselves to be killed in this way shows just how thoroughly, and for just how long, American politics and government have been intertwined with American business. Only through such commingling could the corporate need for profit come to outrank the organic need for a habitable environment. Indeed, what should be noted perhaps above all else in this sordid tale is the way in which the relationship between corporations and the government has been inverted: in the early 20th century, the government asserted its authority and dominated Standard Oil and its ilk; in the early 21st century, ExxonMobil and its kin have dominated the government by co-opting its authority. The parasite has consumed the host, and now both will die.

What we should also make note of is that the case of ExxonMobil is the rule, not the exception. That is to say, the forces hurtling us toward collapse are structural and systemic. They are social problems, not strictly material ones. We can begin to understand this if we ask ourselves, What purpose is the economy meant to serve? Well, economics as a field of study is concerned with the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. But we can dig deeper. In the real world, what problem is an economymeant to solve? The answer here, originally, was scarcity. In a world of scarce resources, an economy is meant to provide a society with the most efficient allocation of those resources. In other words, an economy is a grand strategy for supplying a society with its basic needs. But what happens once those needs have been met? We know, for instance, that we already produce enough food to feed the entire world population. Similarly, today there are far more empty houses in the United States than there are homeless persons. Yet, under the prevailing capitalist economic system, starvation and homelessness remain. The only conclusion to be reached is that these are features, not bugs, within the system. In The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord captures this sentiment with an insightful chiasmus:

“By the time society discovers that it is contingent on the economy, the economy has in point of fact become contingent on society.”2

What Debord means by this is that the capitalist economy — having solved the problem it was created to solve, i.e., scarcity in relation to basic needs — continues through sheer inertia and the creation of false needs to trap society in a system of social relations that have actually become obsolete. (As an aside, this view is being charitable to capitalism in assuming that, at one point, the social relations capitalism prescribed were indeed necessary. That is very much open to debate.) So, the servant has become the master. But this is only possible so long as the people in the society remain convinced that the way things are is the way things must be.

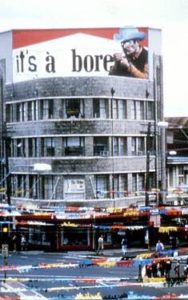

Debord argues that today’s society remains enthralled to the status quo as a result of what he calls “the spectacle.” The spectacle is not just images, like those found in the mass media, though those are important parts of the spectacle. Rather, the spectacle is “a social relationship between people that is mediated by images.”3 The spectacle is the sum total of the multifarious and ever-changing paths of action that direct our lives and that are shaped by images — images produced under the incentives of capitalism, like profit-seeking. When Debord first wrote his book in 1967, one example of the spectacle could have been the prevalence of billboard signs advertising cigarettes — images that might literally convince you to engage in a suicidal activity that you otherwise may never have considered undertaking. Another example that remains prevalent today takes the form of television commercials that flutter rapidly between different, often contradictory messages, confusing, overwhelming, and manipulating the viewer in ways that are not questioned but rather are thought of as normal or even natural. Thus the spectacle, in its totalizing ubiquity, is taken for granted instead of being puzzled over as the historical novelty that it is.

In today’s age, the spectacle plainly extends to the Internet and social media. For instance, image-mediated programs like Tinder and other dating apps shape the ways in which we engage in “romance.” Dating apps, of course, are but one part of a larger social media ecosystem of image-driven apps likeInstagram, Snapchat, and Facebook. These and other apps influence everything from how we interact (or don’t interact) with others in public, to how we eat our meals, to how we conceive of our self-worth. Similarly, Uber and other peer-to-peer apps like Airbnb and TaskRabbit lead us to undertake certain specific social actions at the expense of other actions we might have undertaken instead — impersonally renting an apartment from a stranger, say, rather than reconnecting with an old friend who lives in the city we intend to visit.

All of these actions, in the spoken and unspoken name of efficiency — which is apparently a value by which one’s encounters with other humans should be guided — have given rise to the deceptively named “sharing economy.” (A real sharing economy would be the kind that socialists and syndicalists strive for, i.e., where the means of production are democratically owned and operated by all.) The sharing economy as it exists today, of course, is only the newest mask behind which capitalism hides its obsolescence. As a society, we should know better than to be fooled by this disguise. But our vision is clouded because we have been conditioned by the spectacle to believe that “everything that appears is good; whatever is good will appear.”4 Since we accept or rather are unaware of our enslavement to the social relations demanded by the economy but no longer needed by society, we literally cannot imagine that things could be or should be profoundly, fundamentally different. Indeed, “the spectacle is the bad dream of modern society in chains, expressing nothing more than its wish for sleep. The spectacle is the guardian of that sleep.”5

As soon as society wakes up — as soon as it becomes conscious of the obsolescence of the capitalist economy — capitalism will disappear like the hungry ghost that it is. So, then, awareness of or consciousness of truth, of the real state of things, is what we should be striving toward spreading if we wish to prevent wholesale collapse and extinction. In the Marxian tradition this goal has often taken the form of dispelling false consciousness, or the servile class’s delusion about its position within class society. Historically, organized labor and trade unions have admirably promoted this goal. But, suffice to say, if the labor unions had been successful at combating false consciousness we would not be in the predicament we are in today. Besides, for a whole host of reasons that I will not go into here, organized labor is dead, and it will not be coming back. So, we must turn to other activities that more fittingly correspond to presently existing conditions if we wish to combat false consciousness and spread true awareness about the reality of late capitalist society.

This raises a question about a claim I made at the outset: why can’t we expect political dissidence in the forms of protests, civil disobedience, boycotts, sit-ins, teach-ins, strikes, etc. to accomplish the goal of waking society up? Insofar as these activities result in consciousness raising, they can only be truly successful when they fail. In other words, the problem with these activities — though they have, for instance, helped to spur important historical developments like women’s suffrage and civil rights for blacks, LBGTQ, and other minority groups — is that they have always accomplished their goals within the context of the prevailing system. So these approaches to dissidence can increase freedom, but it is always a bourgeois freedom (which is to say, no freedom at all.) They can produce change within the system, but they have not, thus far, produced a change of system. In fact, by acting as a release valve for social unrest, such movements have tended to perpetuate the existing economic order rather than transform it.

This points to the most insidious way in which these movements — through no fault or intent of their own — have served to reinforce the existing system. By showing to the system the minimal changes it can make so as to pacify social unrest while retaining the system’s structural integrity, these movements have served as the guiding lights that have led capitalism into a future far beyond where it should have gone (i.e., into its current form, neoliberalism.) Debord and his Situationist comrades call this systematic process of neutralization and integration of all authentic critique “recuperation.” Through recuperation the system absorbs within itself and placates on its own terms the complaints that dissidents have lodged against it, erasing the dissidence but preserving the structural conditions and systemic exploitation that gave rise to it. In this way, capitalism shambles forward, becoming stronger from that which did not and could not kill it. We can acknowledge this truth while still honoring the accomplishments of the many brave souls who risked everything to make our immiserated society less miserable.

So, our problem remains unresolved: we desperately need to completely change our entire system of social organization, but none of the old methods of political dissidence will suffice (or certainly will not suffice before the clock runs out on global warming.) What, then, can we do?

We must conduct a massive, rapid transformation of human consciousness. This requires destroying the spectacle. To break the grip of the spectacle, and to prevent the recuperation of resistance, Debord developed the technique of détournement, meaning something like “rerouting” or “hijacking.” Throughdétournement, one turns the various shards of the spectacle back against the spectacle itself. If the spectacle negates life, détournement can negate that negation. (Incidentally, this is how the best humor works: it defies convention and upends our expectations, which is why humor is often subversive.) You’ve seen one example of a particular kind of détournement already, at the top of this blog post. Here is another example:

In general, we can state that détournement is an appropriation of existing media for the purpose of conveying a message that is different than, and generally contrary to or critical of, the message conveyed by the original media. Thus, détournement requires a familiarity with the preexisting image upon which it operates. So, for example, consider the image at the top of this blog post. In order to understand the image, one must be familiar with the Hollywood Sign in Los Angeles. Moreover, this image was created in response to a specific context; namely, an event that occurred this past New Year’s Eve when the Hollywood Sign was modified to read “Hollyweed” (itself an example of détournement.) Being familiar with at least some relevant background information of this kind is necessary for truly understanding any instance of détournement. In other words, détournement is a type of metamedia: it is media that operates on other media and that must be explicitly recognized as such in order to be understood.

This is interesting because, as Marshall McLuhan tells us, the content of any medium is always another medium. That is, speech is the content of writing; writing is the content of print; speech is the content of radio; speech, theatre, and print are the content of television, etc. So, in this formal sense, all media is metamedia, but usually this relationship is implicit; conscious awareness of this fact is not an intrinsic part of consuming the media. (Though there are examples of when this awareness comes into play, such as when characters on a television show “break the fourth wall.”) What is unique and intriguing about our newest medium of communication, the Internet, is that it is obvious to all (even Homer Simpson) that the Internet can have virtually any other medium as its content. The Internet, then, is polymorphic metamedia of the highest caliber: it combines and integrates many (all?) other forms of media as its content, and its users are consciously aware of and can participate in this integration. The truth of this shines through when we strain to imagine an answer to the question, What new form of media could take the Internet as its content?

So perhaps it is no surprise that détournement finds a natural home on the Internet. Indeed, you may have already guessed where I am going with this: memes can be an exemplary form of détournement. Like all forms of détournement, most memes require familiarity with a preexisting image, but they modify that image so as to alter the message conveyed by it in often subversive ways. The connection between détournement and memes is one reason why memes conveying socialist, communist, and anarchist messages are so powerful or, colloquially, “dank,” “spicy,” or “zesty.” This is because the meme form itself, as a type of détournement, is inherently subversive, just like the various leftist political ideologies are subversive in a capitalist society. Take a look through this album and see for yourself:

In all seriousness, then — but also with a healthy dose of irony — I want to answer my opening questions by suggesting that one of the most effective forms of resistance to capitalism and the spectacle that each of us can engage in is the making and spreading of memes. (But, of course, the right kind of memes; we have already seen, with the recent Pepe controversy, how harmful the wrong kind can be.) Remember that the change we are seeking to produce is not the mere modification of the existing system, but the replacement of the existing system with an altogether new system. In other words, we need an act of social creation. To create, we must first shatter the spectacle. This requires a transformation of consciousness among the people living in society — a deep recognition by them that (1) things are not the way that they think they are, and (2) the way they think things are is not the way that things must or should be. Only after breaking free from these two arms of sleep and gaining critical consciousness (conscientization) of reality will people be able to take genuinely revolutionary action.

Détournement, because it requires its percipients to think, has the power to free them from their sleep. Détournement in the form of memes, then, could potentially be the most powerful, most rapidly-spreadingform of subversive art in the history of humankind. For memes are art, and, to paraphrase Maxine Greene, while art may not change the world, art may change people who might then change the world. This is good because, as I mentioned above, if we have any time left in which to transform our society, we have very little time left indeed. So, if you want to help foment the revolution and save life on Earth, do your part: share subversive memes everywhen and everywhere you can.

Here are some sources to help you get started:

Facebook Pages

- Advanced Space Socialism Memes

- Aesthetic Socialism Club

- The Art of Anarchy

- Bro, We Are Communist. Problem?

- Cats Against Capitalism

- Comemenism

- Crapitalists

- Dank and Rare Memes, Also Communism

- Everything is Bourgeois

- Green & Black Anarchists

- Honey, I Shrunk the Bourgeoisie

- Intersectional Imperialist Memes

- Libertarian Marxist Musings

- The Meme Fast

- Purple & Black Anarchists

- Quotes From Capitalists that Inadvertently Provide Support for Communism

- Red & Black Anarchists

- Revolutionary Memes Extreme

- Sassy Socialist Memes

- Seize the Means With Dank Memes

- Shit Bootlickers Say

- Shit Liberals Say

- Socialist Meme Caucus

- Socialist Musings

- Wokémon

Facebook Groups

- Jill Stein Dank Meme Stash

- Karl Marx’s Dank Meme Stash

- Leftist Dank Meme Stash

- Slavoj Zizek Dank Meme Stash

- Sounds Liberal But OK

- Surely This Will Stop Donald Trump

Subreddits

1 Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (New York: Zone Books, 1995), 14.

2 Debord, Spectacle, 34.

3 Ibid., 12.

4 Ibid., 15.

5 Ibid., 18.

- We Are the Threat: Reflections on Near-Term Human Extinction - February 14, 2018

- The Age of Vestigial Politics - August 25, 2017

- The Revolutionary Power of Memes - June 22, 2017